Has World War II carrier pigeon message been cracked?

- Published

An encrypted World War II message found in a fire place strapped to the remains of a dead carrier pigeon may have been cracked by a Canadian enthusiast.

Gord Young, from Peterborough, in Ontario, says it took him 17 minutes to decypher the message after realising a code book he inherited was the key.

Mr Young says the 1944 note uses a simple World War I code to detail German troop positions in Normandy.

GCHQ says it would be interested to see his findings.

Blocks of code

The message was discovered by 74-year-old David Martin when he was renovating the chimney of his house in Bletchingley, Surrey.

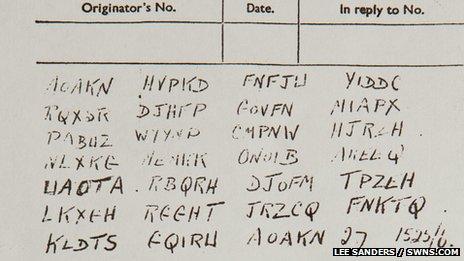

Among the rubbish, he found parts of a dead pigeon - including a leg, attached to which was a red canister. Inside the canister was a thin piece of paper with the words "Pigeon Service" at the top and 27 handwritten blocks of code.

The message - which attracted world-wide media attention - was put in the hands of Britain's top codebreakers at GCHQ at the beginning of November, but they have been unable to unlock the puzzle.

They remain convinced the message is impossible to decrypt, although a spokesman said they would be happy to look at Mr Young's proposed solution,.

"We stand by our statement of 22 November 2012 that without access to the relevant codebooks and details of any additional encryption used, the message will remain impossible to decrypt," he said.

"Similarly it is also impossible to verify any proposed solutions, but those put forward without reference to the original cryptographic material are unlikely to be correct."

However, Mr Young, the editor of a local history group, Lakefield Heritage Research, believes "folks are trying to over-think this matter".

"It's not complex," he says.

Using his great-uncle's Royal Flying Corp [92 Sqd-Canadian] aerial observers' book, he said he was able to work out the note in minutes.

He believes it was written by 27-year-old Sgt William Stott, a Lancashire Fusilier, who had been dropped into Normandy - with pigeons - to report on German positions. Sgt Stott was killed a few weeks later and is buried in a Normandy war cemetery.

'WWI trainer'

The code is simple, relying heavily on acronyms, said Mr Young.

Some 250,000 pigeons were used during the war by all services and each was given an identity number. There are two pigeon identification numbers in the message - NURP.40.TW.194 and NURP.37.OK.76. Mr Young says Sgt Stott would have sent both these birds - with identical messages - at the same time, to make sure the information got through.

"Essentially, Stott was taught by a WWI trainer; a former Artillery observer-spotter. You can deduce this from the spelling of Serjeant which dates deep in Brits military and as late as WWI," he said.

"Seeing that spelling almost automatically tells you that the acronyms are going to be similar to those of WWI.

"You will see the World War I artillery acronyms are shorter, but, that is because, you have to remember, that, the primitive radio-transmitters that sent the Morse code were run by batteries, and, those didn't last much more than a half-hour tops, probably less.

"Thus all World War I codes had to be S-n-S, Short-n-Sweet.

"And, as you can clearly see, Stott got a major report out on a pigeon."

- Published23 November 2012