Peering into the North Korean economy, via satellite

- Published

Amid the current tensions between North and South Korea, much focus has been on their shared industrial zone, where economic output has ground to a halt. The furlough is said to have cost the cash-strapped North some $90m (£58m) in wages, and the South's businesses much more. But as Curtis Melvin, of the North Korea Economy Watch blog, explains, discerning anything about the state of Pyongyang's finances is always fraught with difficulty.

Perceiving what is really happening in the North Korean economy requires one to be creative.

Analysing the country as a visitor is difficult as you are kept under tight supervision. Unforeseen events can shake things up, but for the most part you will be shielded from unapproved activities.

Unwrapping North Korea through public data is even more difficult, as the country does not publish a budget and rarely does it release any meaningful economic or social statistics.

But the opacity of the secretive state's system, however, has opened the door for researchers to gain valuable insights from commercially available satellite imagery.

The analysis - by social scientists and economists - of the North's burgeoning market economy is a case in point.

Socialist ideology 'contradicted'

When China and Russia ended subsidies to North Korea in the 1990s, the official economy collapsed, famine ensued and traditional farmers' markets grew to fill the economic void.

The North Korean leadership remains uneasy about the spread of these markets because they operate in contradiction to the state's socialist ideology, and more than anything else, these markets broke the government's monopoly on information by distributing illicit foreign goods.

They are permitted to exist, however, because they are an economic necessity for the people and, now, a secure source of revenue for the state.

In a survey of North Korean defectors - published by Haggard and Noland in 2011 - 69% of respondents reported that over half of their income came from market activities, as opposed to employment in the government or state-owned enterprise.

Only 4% of respondents reported that none of their income came from market activities.

The survey population, however, was overwhelmingly composed of refugees from North Korea's north-eastern provinces. What about the remainder of the country?

Satellite imagery shows the Haggard/Noland findings are plausible nationwide.

Backbone of economy

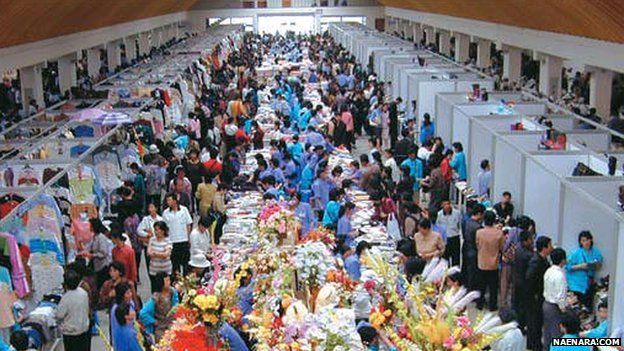

Analysts have identified well over 300 markets across North Korea. Many are larger than a standard football pitch. Satellite imagery also shows these markets are growing.

By layering historical imagery we can observe markets that were small in the early 2000s are now taking over their neighbourhoods.

We can estimate the number of vendors in some of these markets - giving us a lower-bound estimation of the size of the local merchant class.

What we observe is that having existed only at the margins of the North Korean society in 1990, North Korea's markets are now the backbone of the consumer economy.

Satellite imagery analysis also sheds light on Pyongyang's ability to enforce market regulations outside of the capital.

In many cases where Pyongyang has ordered markets to be closed we can see thousands of people trading at "grasshopper" markets in makeshift locations. These spontaneous markets represent a double-loss for the regime.

From an ideological perspective, people are engaging in self-directed capitalist enterprise.

From a public finance perspective "grasshopper" markets represent lost revenue to the state because the government does not sell slots at the official marketplace.

'Mining boom'

Satellite imagery also sheds light on North Korea's continued economic integration with China.

Statistics Korea reports that Chinese trade with North Korea totalled $5.63bn in 2011 (up 284% from 2007), and exports to China totalled $2.46bn in 2011 (up 424% from 2007) - primarily composed of coal and iron.

Satellite imagery of North Korea is not perfect. Many parts of the country go unobserved and many times only older imagery is available to analysts.

Today, however, we can identify no fewer than 80 new mining projects have been undertaken in the last seven years.

These new projects consist of both renovations to existing mines and the construction of new pits. The scale of investment requires a large influx of foreign capital because the DPRK simply lacks the finances and capacity to bring these mines on-line by itself.

Satellite imagery has also been a vital tool for NGOs and rights groups who are tasked with monitoring changes in North Korea's notorious political prison system.

In 2003 the Committee for Human Rights in North Korea was the first organisation to publish a comprehensive report on the North's political prison camps.

The existence of these camps was verified by matching defector testimony and hand-drawn maps with satellite imagery of the related areas.

Since 2003, however, we have witnessed a dramatic change in the way North Korea manages its political prisoner population.

Defector testimony, clandestine reporting and satellite imagery have been used to confirm that North Korea has closed Camp 22 in Hoeryong and Camp 18 in Pukchang.

Unfortunately, no information has yet to lead us to a definitive conclusion about what has happened to the former inmates.

And it is not all good news on this front, however. It is only through satellite imagery that we learned in January of this year that North Korea had expanded its incarceration capacities at two other prison camps, No 14 in Kaechon and No 25 in Chongjin.

As no information about these facilities has been obtained from within North Korea, satellite imagery is our only tool for recording these changes.

Satellite imagery offers a new and accessible source of data for analysing North Korea. Now everybody with an internet connection can observe the most remote corners of the country, or track North Korean projects in distant corners of the globe.

Try it for yourself and share with the world what you discover.