In October of 2010, the smartphone patent wars were heating up. That month, Microsoft filed a complaint against Motorola at the International Trade Commission saying various Motorola phones violated its patents. Motorola shot back with patent demands of its own, saying that Microsoft owed it a heap of cash for Motorola patents related to the H.264 digital video standard and the 802.11 wireless standards. In fact, Motorola wanted 2.25 percent royalties paid on an array of Microsoft's most profitable products, including Windows and Xbox.

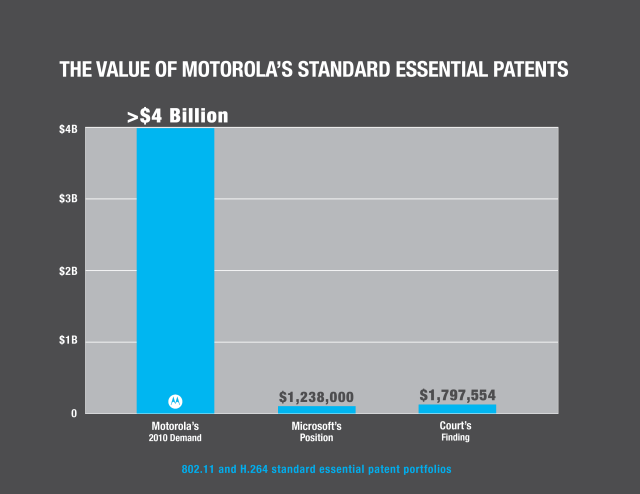

The problem was, Motorola had agreed to license those patents at so-called "reasonable and non-discriminatory" or RAND rates. Microsoft accused Motorola of breach of contract, saying that Motorola's 2.25 percent demand was anything but the "reasonable" rate Motorola had promised. Microsoft calculated that it would result in a $4 billion payment.

That led to a lengthy lawsuit and a trial in November 2012, meant to answer a simple question: just what exactly does a RAND promise entail? It's a big issue, because as patent battles between competitors heat up, more patents tied to industry standards are being used as ammunition. Samsung used standards-essential patents (or SEPs) against Apple in its blockbuster trial, but to no avail. And Motorola has used them, against both Apple (in a case that was shut down just before trial) and Microsoft.

Now US District Judge James Robart has made a decision as to just what "reasonable and non-discriminatory" will mean, and his definition is much closer to Microsoft's point of view than Motorola's. In fact, with yesterday's order, Motorola lost nearly all of its leverage when it comes to using standards-based patents. So did other companies, especially Android-using smartphone companies, that want to use such patents to defend themselves from Microsoft or from Apple.

The public version of Robart's 207-page order [PDF] was released last night. He provides both a specific rate and a range in which the rates might vary a bit. The key findings:

- For Motorola's H.264 patent portfolio, Microsoft will have to pay 0.555¢ per unit, for products like Windows and Xbox. The range will be from 0.555¢ to 16.389¢ per unit.

- For Motorola's 802.11 patent portfolio, Microsoft will have to pay 3.471¢ per product. The range will be from 0.8¢ to 19.5¢ per unit.

Even at the high end of the "ranges," those numbers are far, far lower than what Motorola was asking for.

Robart arrived at them by looking at a wide array of licenses Motorola had struck with other companies, as well as rates used by industry patent pools. But in cases where Motorola was able to point to a 2.25 percent rate being paid—for example, in a licensing agreement with competitor VTech—Robart noted that those agreements involved much more than just the patents at issue here. VTech, for instance, was able to achieve a widespread patent peace; it took a license to Moto's 802.11 and H.264 patents "only as part of a package deal in which it also resolved Motorola's infringement claims."

Hardly anyone can claim to have digested the whole 207-page order quite yet. But Judge Robart "appears to have based much of his determinations on rates offered by patent pools (the MPEG LA AVC/H.264 pool and the Via Licensing 802.11 pool), as well as license rates charged by chip designer ARM Holdings," wrote Matt Rizzolo, a Dow Lohnes attorney who has followed the case closely. (Rizzolo's blog also has a helpful timeline of the whole Microsoft v. Motorola dispute.)

A Motorola spokesperson responded to the judge's decision by saying: "Motorola has licensed its substantial patent portfolio on reasonable rates consistent with those set by others in the industry."

Setting a precedent: from $4 billion to less than $2 million

Motorola had mounted a serious counter-attack: it was asking for up to $4 billion in royalties annually on Microsoft's most profitable products. Now, the sting of that counter-attack has been removed.

Microsoft has sold 66 million Xbox 360s, for example. Even if it had to pay the judge-set royalty on every single one (and it won't), that would come out to a bit more than $2 million, a small drop in the bucket for the software giant. Microsoft's own calculation says it will owe about $1.8 million annually under Robart's rules, less than half a percent of what its opponent was asking for.

Motorola's request of 2.25 percent would have worked out to $4.50 on a $199 Xbox. Instead, it will be entitled to 3.5¢. It's a staggering difference that almost destroys the idea of Motorola using standards-based patents as strong ammunition in the patent wars. $2 million generally won't cover big-firm legal fees in even one patent case, not to mention all-out patent wars that involve multiple actions at the International Trade Commission as well as district courts.

To no one's great surprise, Microsoft quickly issued a press release stating it was pleased with the findings. "This decision is good for consumers because it ensures patented technology committed to standards remains affordable for everyone," said David Howard, a deputy general counsel for Microsoft.

Now that the rates have been set, the next step is to decide whether Motorola breached its contract by trying to squeeze $4-6 per Xbox out of Microsoft when it was actually entitled, by Robart's calculation, to less than one percent of that. That could go to a jury or it could be decided without one. Microsoft will have to show that Motorola's 2.25 percent demand was "blatantly unreasonable" compared to the RAND rates Robart just set. Given the great distance between what Motorola wanted and what it got, the breach of contract case is looking good for Microsoft. Trial on that issue is currently set for August.

However that turns out, Microsoft already has what it needs from this case. It has neutralized one big patent counter-attack, and may have foreclosed others in the future. When smartphone companies began using patents to attack each other in earnest a few years ago, companies like Samsung and Motorola wanted to fight using the best "ammunition" they had, and they often decided that was the patents they had that were connected to various standards.

Now, they'll have to turn to other kinds of patents in their vast reservoirs. But they've got them.

This case has been closely watched in the patent world, because while thousands of patents are under RAND commitments, no federal judge had actually made a ruling saying what RAND means. Other judges won't be bound by the numbers that Robart came up with, but given his court has considered the issue more extensively than any other, they may well use his numbers as a guideline.

reader comments

177