Editor’s Note: For more on this issue, tune into “Sanjay Gupta MD” at 4:30 p.m. ET on Saturday and 7:30 a.m. ET on Sunday.

Story highlights

Former NFL players Wayne Clark and Fred McNeill participated in a UCLA study

The protein tau, linked to a brain disease, was found in both of their brains

McNeill has early-stage dementia; Clark does not

Researchers say other variables may come into play when it comes to the disease

About a year ago, a former quarterback with the San Diego Chargers and a retired linebacker with the Minnesota Vikings lifted their once-sturdy frames onto a cold examination table.

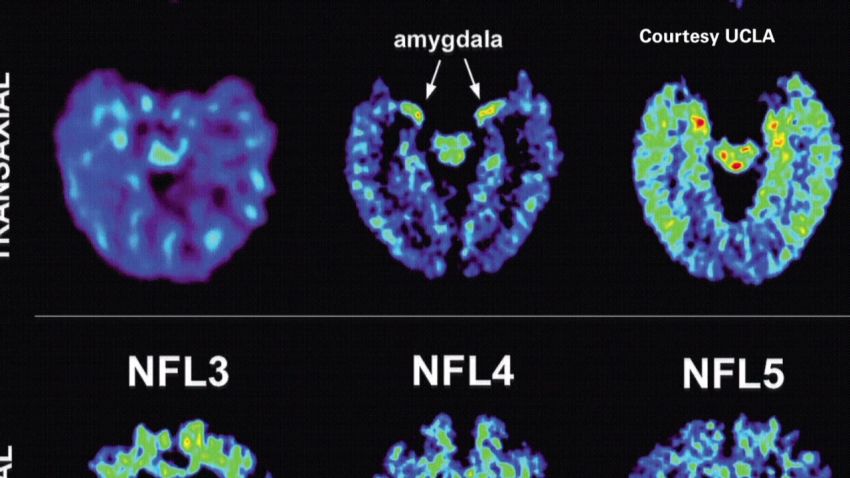

Meanwhile, a radioactive chemical was coursing through their bodies on its way to receptors in their brain tissue. A hum filled the room as each man slid toward a doughnut-shaped opening on a brain scanner. When their scans were later analyzed, crimson and bright yellow bands appeared deep in their brains, indicating damage.

The two former players, Wayne Clark and Fred McNeill, were participants in a pilot study at UCLA that may have found a destructive protein called tau in the brains of five living retired National Football League players.

Tau is significant because it has been found – posthumously – in the brains of dozens of former NFL players, including Junior Seau, Dave Duerson, Terry Long, Shane Dronett and Mike Webster. All committed suicide and were later diagnosed with a disease called chronic traumatic encephalopathy.

Some scientists call finding the disease in the brains of living players the “holy grail” of CTE research, a way to diagnose and treat it. The UCLA study may turn out to be an important first step in that effort.

But at this early juncture, the small study poses more questions than answers. Consider McNeill and Clark. Study authors say both had tau in their brain tissue, yet they are on opposite ends of the cognitive spectrum. McNeill, 60, has been diagnosed with early stage dementia, while Clark, 65, is cognitively normal.

Lamar Campbell: Why I’m donating my brain

“The sample is too small, and we don’t know enough to make much sense about this,” said Dr. Gary Small, lead author of the study, which appeared last week in the American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry.

Clark’s brain scan – as crude a picture as it provides of his brain function – showed bright patches of red and yellow in key areas of the brain associated with rage, depression and memory problems. The hypothesis of the study is that the more concentrated the tau protein, the more red and yellow appears on the scan.

Yet Clark says the worst thing that happens to him daily is occasionally forgetting the name of someone he just met.

“He’s in his mid-60s and just has normal aging, has mild memory complaints typical for somebody that age,” said Small, professor of psychiatry at the Semel Institute for Neuroscience and Human Behavior at UCLA. “So we need to do more studies of players with symptoms, more studies of players without symptoms, and see what the correlations are.”

In contrast to Clark’s scans, McNeill’s were flecked with red here and there, but most of his scan was greenish in hue, suggesting less tau.

When his wife got the news that researchers may have found tau in McNeill’s brain, she was anything but surprised. His cognitive decline has been slow and, at times, painful.

But when Tia McNeill, who is separated from her husband, considered the possibility that another player has tau but no cognitive problems, she remained unfazed.

“I think that as with anything, our bodies are all different,” she said. “There are some players that are deeply affected and other that aren’t.”

Scan may detect signs of NFL players’ brain disease

She knows that story well, recalling McNeill’s roommate when he played for the Vikings. “They entered the league the same year, played the same position, used the same equipment, had the same coaches,” but today the former roommate is cognitively normal.

Clark and McNeill are around the same age, but that’s where their similarities end. Clark started playing football in high school and was not a sought-after college recruit. He made it to the NFL and mostly lingered on the sideline as a backup quarterback.

“I didn’t personally feel at risk at all because I didn’t take the steady contacts that other players did,” Clark said.

McNeill, on the other hand, began playing at a younger age, was a first-round draft pick when he entered the NFL, and by the time his career ended in 1985, he had played football for more than 20 years.

Quarterbacks like Clark – especially backups – get nowhere near the number of hits linebackers like McNeill suffer. In fact, the highest-profile cases of CTE thus far have primarily been diagnosed among linemen and linebackers, positions where hits to the head occur on virtually every play.

“One of the arguments is that it may have less to do with the number of concussions but more the number of sub-concussive impacts over the course of a player’s career,” said Kevin Guskiewicz, director of the Center for the Study of Retired Athletes at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

That might explain Clark’s lack of symptoms.

NFL Players Association, Harvard planning $100 million player study

Another popular theory among researchers is that the stark cognitive difference between players like Clark and McNeill could boil down to genetics.

Small points out that when it comes to Alzheimer’s disease, which shares some symptoms with CTE, there are certain genes, like ApoE4, that predispose people to worse cognition.

So could McNeill be genetically more vulnerable to cognitive problems? Or was it the sheer number of hits he took to the head compared with Clark?

“Everything needs to be put on the table,” said Guskiewicz, a concussion expert. “It may be something environmental, it may be genetic. What we need to focus on is what creates this perfect storm.”

Small is realistic about the study – despite his confidence in the early findings – and the need for much more data to explain what that perfect storm looks like.

“I would say to (Clark), ‘Yes, I know that you have a scan that looks different,’ but we don’t know what that means yet,” Small said. “What I suspect is that it’s not just the scan. There may be a lot of other variables that come into play that determine whether there’s a close correlation between the tau deposits in the brain and any clinical symptoms.”

Former football star Junior Seau’s family sues NFL, Riddell helmets