Spy scandal in Moscow evokes an earlier era

- Published

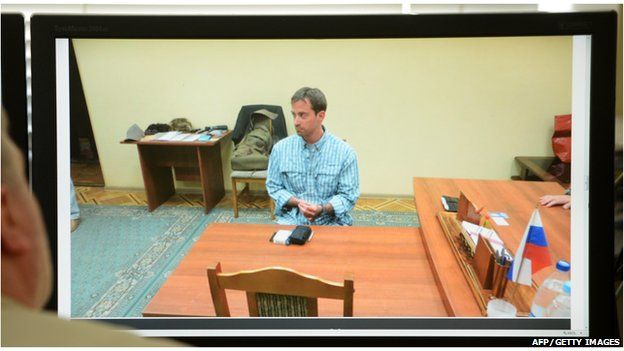

The arrest of Ryan Fogle in Moscow shows that the Cold War is not over. For some, that is reassuring.

The kit was primitive - two wigs (tousled blond and dark brown), sunglasses and a compass.

It all belonged to Ryan Fogle, at least according to Russia's Federal Security Service (FSB).

They claim that he worked for the CIA.

The accusation was serious: espionage. But as kits go, this one was nothing special.

The wigs, sunglasses and other items were placed on a table, shown in a photograph that was published by the Kremlin-supported news channel Russia Today.

"It sort of looked funny," says Angela Stent, who is director of Russian studies at Georgetown University.

"And the wig - I thought that was pretty interesting," says Stent. "You'd think in the 21st Century they would have something different."

If the kit seems dated, so does the Russian government's strategy. Officials detained Fogle and then said that he was "persona non grata" and had to leave Russia.

It was fiery rhetoric - from a different era - and also troubling for statesmen.

The media storm over Fogle, who worked as the third political secretary at the US embassy in Moscow, is an unwanted distraction for diplomats.

President Vladimir Putin and President Barack Obama have meetings planned for the coming months - one in Northern Ireland and another in Russia.

Few people expect that the arrest of Fogle will interfere with these plans. Nevertheless, the situation makes relations between the US and Russia more complicated.

For historians and Russia observers, though, the arrest of a US official is nothing new.

Throwing alleged spies out - and creating a diplomatic spat - is a tactic that dates back to the Cold War.

"They expel some people, and then we expel some people," says Stent.

"Even though we're more than 20 years away from the Cold War," she says, "we're still doing this to each other."

No Russians have been expelled from the US. But there are previous examples of "tit-for-tat" deportations, as she puts it.

In 2010, for example, officials in Washington and Moscow worked out a spy deal.

Ten Russian agents, including Anna Chapman ("red-hot beauty", as the New York Post described her) were expelled from the US.

In exchange, four prisoners who had been convicted of treason were allowed to leave Russia.

It was a dramatic moment in history.

"It was almost like a TV programme," says Peter Earnest, a former CIA officer who is now executive director of the International Spy Museum in Washington.

"Afterwards there was a TV programme," he says.

The Americans, a television series about KGB spies who are living undercover in the US, premiered on FX in January.

It takes place during the Cold War, tapping into an enduring interest that people have both in espionage and in the period of time when nuclear war loomed in the background.

This week, the announcement that Fogle, an alleged CIA agent, had been caught in Moscow seemed as if it were produced for television.

It even included footage of Fogle that was shown on Russia Today.

The video had a familiar look. The capture of a spy overseas, or at least accusations against a US diplomat, is a ritual for officials, one that has been repeated over the years.

That makes sense. Tactics that seem quaint, whether in espionage or statecraft, are still used by officials for one reason: they work.

Plans for kicking out an alleged spy are sometimes sorted out beforehand - behind the scenes - and sometimes afterwards, says Stent.

It is a familiar sequence - and helps to reduce tension. When everyone knows what to expect, the geopolitical situation can remain stable.

And just as modern-day statecraft sometimes relies on a traditional model, so does intelligence gathering.

Former intelligence officers defend Fogle's kit. They say that in espionage, old-fashioned tools may be better than sophisticated ones.

People are less likely to recognise you in a wig and sunglasses, and these objects are also practical. You can stash them in a carry-on.

"Let me tell you, baby, running an operation in Moscow is a very difficult thing to do," says Paul Redmond, a retired senior CIA officer who used to be their chief spy hunter.

"You've got 24-hour surveillance, and you have to go through all sorts of things to get out - that involves disguises and everything else," he says.

Besides that, simple devices are less likely to be hacked or discovered.

"People might say, 'oh, didn't that go out with the Cold War?'" Earnest says. "But that does not rule out traditional means - if circumstances call for it."

This week, officials in Washington and Moscow are trying to resolve the crisis over Fogle. But not everybody is surprised or dismayed by the events.

Redmond says that the presence of Moscow agents in the US in 2010 - the "illegals", as they are known, was a sign that "the Russians are still at it".

Russia experts in the US agree. They say that Moscow officials have ramped up their spy work in other countries.

"The activities of Russian intelligence agents abroad have increased," Stent says.

Some may have thought that Fogle's alleged kit - wigs, sunglasses and other objects - seemed quaint.

For Redmond, though, the wig and sunglasses were a positive sign.

"It's nice to see that the US is still trying to collect intelligence," he says.

The Cold War continues, at least for diplomats, and certainly for the spooks.

- Published24 January 2006

- Published3 February 2003